In 1916, when Nolte Precise Manufacturing opened the doors of its Cincinnati, Ohio, business as a screw machine shop, the founders would be hard pressed to recognize that business as it exists in 2018. Needless to say, 102 years of continuous operation is something to admire, but more importantly, it raises the question of what management has done to secure that legacy.

When Nolte started, the screw machine industry was somewhat distinct from the general machine shop industry. In some ways it was more advanced in part because the use of automatic machines, which were actuated by cams and designed to run continuous production, could often outpace the shorter production runs that needed more flexibility and more operator oversight.

Featured Content

This dichotomy of medium to high continuous production versus small lot sizes with multiple change-overs continues today, but it’s a very different animal than it was for much of the 20th century. The reason being that the definition of medium-high production has changed significantly. In many industries, shorter product life cycles have resulted in the overall shrinkage of lot sizes (requiring more frequent change-over) and has impacted the production technology that the screw machine industry relied on for many years, moving it closer to the flexibility side of the equation.

As a result, shops like Nolte have needed to change or perish. The family that owns Nolte chose to change, and as a result, will celebrate its 103rd birthday in 2019. We sat down with Doug Coster, Nolte’s fourth generation owner and president, to discuss the company’s ability to adapt in the past, present and future.

So Many Choices

For much of the history of Nolte Precise, the definition of a screw machine shop was pretty straightforward. It meant a shop’s primary work was turned parts, often relatively simple and usually in large enough quantities that machines could be set up and dedicated to production of a single job or set of jobs for a given customer.

The machine tool technology was built around cam-actuated slide movements that demanded specific skills and a lot of time for setup. Once it was set, the machine could run “automatically” for significant times with little operator interference.

Product life cycles were much longer and a given set of basic part specifications could remain virtually unchanged, sometimes for years. Screw machine shops did well for many years. However, that business model eveolved and survivor shops such as Nolte were able to recognize that change and change with it.

Mr. Coster says when he joined Nolte, the shop, like many screw machine shops, was running automatics. It ran about 40 Brown & Sharpes, of which the company has three of those machines left on the floor today.

“We began the transition from cam to CNC slowly,” Mr. Coster recalls. “Our first CNC Swiss was purchased in 1994 specifically for a job we had won the contract for. It was a more complex part and tighter tolerance than much of our normal work, but indicated the direction we needed to take the company strategically.”

Another confirmation that the handwriting was on the wall in the 1990s for the traditional screw machine shop, as it was defined for many years, came with the name change of the trade association for screw machine shops, which included Nolte and many other shops like it. The association went from the National Screw Machine Products Association to the Precision Machined Products Association. Nolte has been an active member of the association since 1943.

“With the addition of CNC machining capability, we began making the infrastructure change, which over time required replacing the cam department with CAD/CAM programming capability. We standardized with DP Technology for our offline programming,” Mr. Coster says.

Many screw machine shops, including Nolte, discovered that with the infrastructure shift to CNC programming capability, non-traditional machining operations became doable. Unlike cam setting, G code doesn’t care what kind of machine it is running.

Doing More

Today, Nolte’s portfolio of customer services include CNC turning, CNC Swiss machining, CNC milling, sub-assembly and single-spindle/multi-spindle automatic screw machining for medium to high volume production quantities. These expanded operational capabilities allow for an expansion of the company’s customer base attracted a broader number of industries served by Nolte.

“We generally don’t purchase machines without the work to put on them,” Mr. Coster says. “However, having expanded our shop’s capabilities into more varied operations, we are able to attract work from our customers that might have otherwise gone to another shop.”

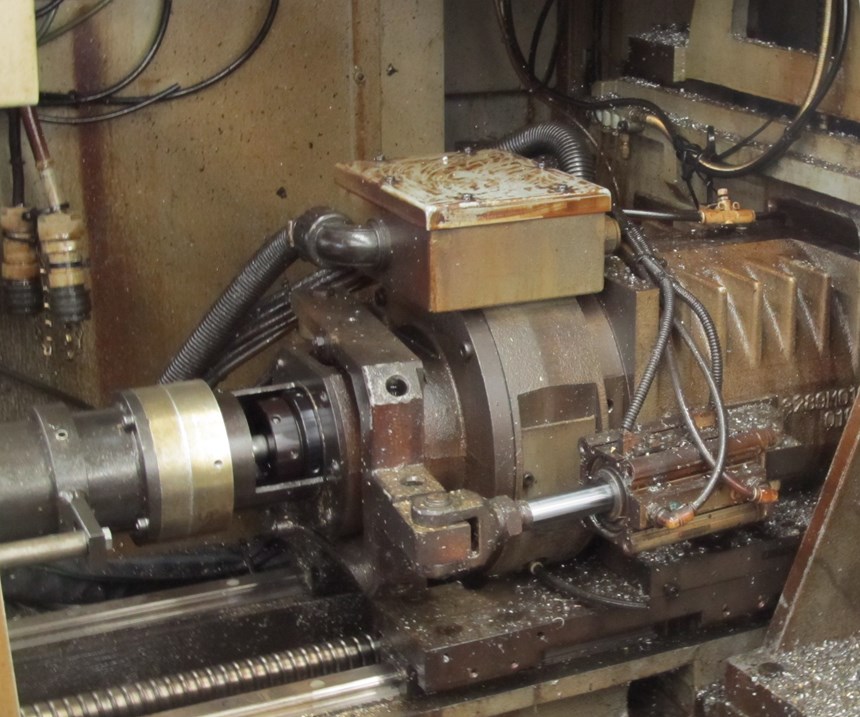

The centerpiece of Nolte’s machining capability is its proficiency with managing production of complex parts across its CNC Swiss machines. After running several brands of CNC Swiss, in 2013 Nolte standardized its shop with Tsugami machines.

“Our newest Tsugami machine is a model BO 206,” Mr. Coster says. “It’s a 20-mm machine with six axis, opposed gang tool setup. It is also equipped with a chucker package that gives us the flexibility to run the machine with or without a guide bushing as dictated by the length-to-diameter ratio of the workpiece. Many jobs run better on a sliding headstock machine even though they are not traditional Swiss-type parts. The key is dropping off the part complete as possible using a single handling.”

One reason that Mr. Coster believes in focusing on a single brand, such as Tsugami, is the familiarity that the programmers, setup people and operators can establish experience with one brand. Over time, they are able to become proficient with these machines instead of relearning the idiosyncrasies of different brands. The FANUC control that Tsugami uses is also an advantage to standardizing because most of Nolte’s people are familiar with it.

Whenever possible, Nolte engineers the work flow to keep quality at a high level while reducing excess manufacturing costs and cycle times from multiple part handling. This is a result of having the right equipment for part processing and personnel familiar with getting the most out of it. “It doesn’t matter if it’s Swiss turning or four-axis milling; if we can set it up once and take labor out of running it, we’re saving time, money and producing quality parts more consistently,” Mr. Coster says.

Moving to Lights-Out Production

Making good parts during hours that would historically be considered downtime, using little or no labor, is enough to tempt any CNC machine shop. That’s where Nolte is heading with its Swiss machining production.

“Currently, we are running up to five of our Swiss machines untended,” Mr. Coster says.

But untended production is not as simple as flipping a light switch from on to off. There are steps that a shop needs to put into place to successfully execute lights-out manufacturing. Probably the most important is selecting the right job to run across the machine tool. Nolte runs a variety of materials and while free-machining materials are ideal for untended machining, the process has to be honed to accommodate other materials that are more difficult to machine.

“We are not exclusively a brass shop,” Mr. Coster says. “So we need to be able set up our jobs so tool wear can be accommodated. Sometimes, we’ve found, pre-hardened steels and other harder materials may actually run better than the softer materials.” One way they prepare for a stable process, eliminating variability, is to run ground barstock across the Swiss machines when the guide bushing is used. This helps with tool wear by reducing variability bar to bar.

An advantage that the convertible model BO 206 brings to the process by eliminating the need for a guide bushing, is that it allows the use of cold-rolled barstock. Not having to use ground stock and eliminating the need to set the guide bushing saves material costs and setup time because the spindle nose collet is more forgiving of stock variations than a guide bushing.

In addition to making sure the machine tool program running the part untended is stable, there are other ancillary considerations that Nolte takes into account for its lights-out operations. The company’s Tsugamis are equipped with FMB bar feeders with magazine feeder trays. Depending on the bar diameter, these magazines can hold enough stock to get the machine through a lights-out shift.

To help control chips, Nolte uses high pressure coolant (Nolte cuts with oil) for all of its Swiss machines. This controls chip formation and evacuation, which is important for untended operation. Nobody wants a bird’s nest in the middle of the night.

There is a serious concern of the possibility of fire during a lights-out operation, especially when cutting with oil. Therefore, Nolte has equipped all of its Swiss machines with fire suppression systems.

Without operator intervention, handling finished part output can be overlooked. Some of the parts that Nolte runs across its lights-out Swiss machine have a no-marr spec, making post-process handling part of the operation. For these jobs, Nolte uses a rotary accumulator to more carefully handle and sort the work coming off the machines.

Lights-out manufacturing is a risk/reward undertaking. The rewards can be great if risks can be minimized. This means making mistakes and learning from them.

Looking Forward

Nolte has seen a lot of change in metalworking manufacturing. It has also managed to successfully adapt itself to these changes by carefully evaluating what works and what may be transitory.

The next investment that Nolte plans to make is to automate the company’s chucked part operations. Barstock is certainly important to the shop’s capability, but Mr. Coster sees the capability of process slugs and automating the material handling of chucked parts as a direction moving forward.

“For example, we have ordered a gantry-fed turning center for processing larger, 3.125-inch and above, chucked blanks as part of our plans,” Mr. Coster says. “Moreover, we are looking at robots to help with automation on our other machining operations.”

Moving forward, Mr. Coster plans to continue focusing on automation as it makes sense for his shop. “One of the benefits that Nolte has enjoyed from its lights-out operations is that the workforce has remained in place, but re-deployed within the shop to more value-added work,”

Mr. Coster says. “Everybody is experiencing skilled work shortages, so keeping good workers and creating an environment that people want to work in is a key to managing for the next 102 years.”

Nolte Precise | 513-923-3100 | nolteprecise.com

RELATED CONTENT

-

Manufacturing Data Collection and Management Transforms Swiss Shop

A New Hampshire high-volume precision solutions manufacturer and an innovative software solutions provider have collaborated in upgrading the shop’s data collection and organization methods, maximizing output and competitiveness.

-

Moving Up To CNC Swiss Screw Machines

Three new CNC Swiss machines in 18 months have provided real growth for this Illinois shop.

-

Dry Swiss Machining in Medical

Continuing to build its reputation for creative solutions, this multi-faceted medical device component manufacturer took its Swiss machining operations to a new level to meet a customer’s market demands.