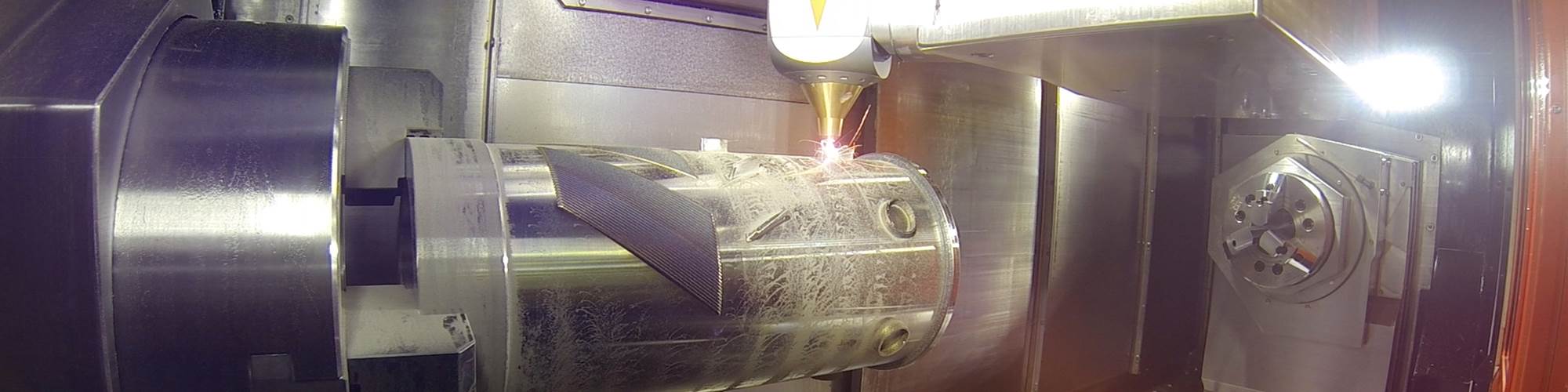

The laser cladding head for WFL Millturns install directly into the machines’ B-axis spindles. Photo credit: WFL Millturn Technologies.

Additive manufacturing (AM), technology that builds 3D components layer-by-layer, continues to evolve. Once a tool primarily used for prototyping parts in plastics, it is starting to impact the manufacturing design and production world in a more significant way with the advent of metal parts printing. In short, this technique offers advantages in that it can produce complex, contoured designs that would be challenging, if not impossible, to create on conventional machining equipment (such as conformal cooling channels inside injection molds). Part designs can also be refined for reduced weight while retaining (or enhancing) structural integrity by applying concepts such as generative design.

That said, AM is a technology that complements machining, but won’t replace it. Interestingly enough, there’s no clearer way to punctuate this point than to look to the increasing number of machine tool builders adding additive to their subtractive equipment platforms.

Virtually all AM-built parts need some sort of postprocessing operations. This might entail milling, drilling, tapping or turning as well as grinding or polishing. By combining additive and subtractive on one platform, work-in-process can be eliminated as well as the capital equipment required to complete an additively grown part. Plus, AM can be used to add small, complex features to large, machined parts. Or, for repair work, material can be added to worn parts that could then be machined away to bring them back to OEM specifications.

Videos below show these types of applications. For example, AM processes such as laser cladding have been added to various machining platforms, including turn-mills and five-axis machines. An accompanying video online shows an example of the former: a WFL M80X Millturn in which the laser head installs into the B-axis milling spindle to add material to a very large component. Laser hardening of select features can be performed, too.

In this case of a Mazak Integrex i-400SAM shown using additive to add features to a long feedscrew component, the AM laser deposition head (three are available with varying beam diameters for this model) is not mounted in the machine’s B-axis milling spindle. Instead, it installs in a dedicated, pivoting unit, and unused laser heads are stored outside the workzone, much like tools would be in a machining center’s automatic toolchanger carousel.

Another video shows an example of repair work. In it, a five-axis Tongtai AMH-630 uses an AM laser cladding head that fits into the machine’s milling spindle to deposit Inconel 718 material onto the worn tips of turbine blades that is then machined, leaving behind the OEM-specified contoured shapes.

Software for these hybrid applications continues to evolve, too, just as the hardware does. This is demonstrated in a video that shows the production of an Inconel 625 blisk using Autodesk Fusion 360 and PowerMill software on a Mazak Variaxis J-600/5XAM hybrid machine using Seco Tools’ solid carbide and ceramic tools. Rather than starting with a large billet of material that will be machined away to create the blisk, the workpiece starts with the hub and the blades are then additively grown and machined to shape and size.

Still, how do you program a multitasking machine with additive capability? A lengthy but informative video takes you step-by-step through the programming process for a rotary part with blades created via AM and then subsequently finish-machined using Siemens NX CAM.

And, what about offline simulation that is so important to complex machining work? CGTech’s Vericut additive module simulates both additive and traditional machining (milling or turning) capabilities of hybrid machines using the same NC code. It reads the laser parameters, controls’ laser wattage, flow of carrier gas and metallic powder specific to each job and material type, then detects possible collisions between the machine and additive part as it is being printed which is described in another video.

Of course, there is the opportunity to add AM heads to various other types of machine platforms. For instance, 3D Hybrid Solutions can supply add-on heads for metal 3D printing via various methods of deposition, including laser melting of powder spray, arc melting of wire feed and high-velocity cold spray of metal powder. It seems this idea has the approval of the U.S. Marines as explained in this story.

Is metal AM on your radar? Or, are you using 3D plastic printers in your shop for prototyping, jigs, fixtures and more? Send me an email at dkorn@productionmachining.com to let me know.

RELATED CONTENT

-

The Evolution of the Y Axis on Turn-Mill Machines

Introduced to the turn-mill machine tool design in about 1996, the Y axis was first used on a single-spindle, mill-turn lathe with a subspindle. The idea of a Y axis on a CNC originated from the quality limitation of polar interpolation and the difficulty in programming, not from electronic advances in controls or servomotor technology as one might commonly think.

-

Custom Tooling, Workholding Help Whip Rotors Into Shape

Whipple Superchargers uses unique form tools and dead-length-collet workholding for its B-axis turn-mill enabling it to create more accurate rotors for its brand of engine power-adders.

-

Does A Turn-Mill Have to Turn?

Here’s an example of a shop applying innovative probing, tooling and workholding strategies to enable its turn-mill to machine castings complete.