Craftsman Cribsheet No.116: Twist Drills for Success

Drilling holes is one of the most fundamental operations we do in machining.

#pmpa

In today’s world, it seems that all information is tailored toward carbide drills. Carbide drills are great, but how many do you really use every day? Especially in our small-to-medium quantity job shops? It is likely that we use mostly standard HSS twist drills. It is not economical to buy expensive carbide drills for shorter-to-intermediate runs. The problem is that most of the available data and recommendations are tailored toward carbide drills. It is important that we still understand the basics of twist drills. How do you know when to use what type of drill? What is the geometry you want to have? What type of flute do you want to use?

In carbide drilling it is recommended to pilot instead of spot drilling. On the other hand, with standard twist drills it is generally recommended that we spot drill — following with angles that are greater than or equal to the last drill point. For instance, follow a 90-degree spot with a 118-degree drill. If you drill with a 135-degree parabolic, you can’t follow with a 118-standard drill — it will walk off center. This can be especially important for parts with multiple inner diameter dimensions, and using non-carbide drills.

Featured Content

When drilling in tougher materials (such as stainless, high-carbon steels and most alloys), multifaceted grinds help reduce the cutting forces at the tip and help to pull the chip. This is where parabolic drills shine. Today, almost all parabolic drills are made with split points enabling them to be self-centering. I have found it is better to spot drill even when using a split point drill. The parabolic drill enables chips to flow out of the hole rapidly while still permitting coolant to reach the tip.

If the hole is greater than 3 to 4 times the drill diameter, I would recommend pullouts. With HSS twist drills, pull all the way out of the hole to allow the coolant to flood the hole and remove chips. This will also enable the tip of the drill to cool before reentering the cut. On CNCs with modern G83 peck cycles, I like to pull out to .100” in front of the hole. There is a small dwell on the pullout of the peck cycle, but if you are drilling tough material it would be beneficial to increase the dwell. Write your own cycle-increasing dwell times. Also, you can get the optimum pullouts going 3.5X drill diameter first peck, 2X drill diameter on the second peck then about 1X drill diameter (1-1.5X diameter) on all pecks after the second peck. The deeper the drill goes the more difficult it is to remove chips and get coolant to the cutting tip.

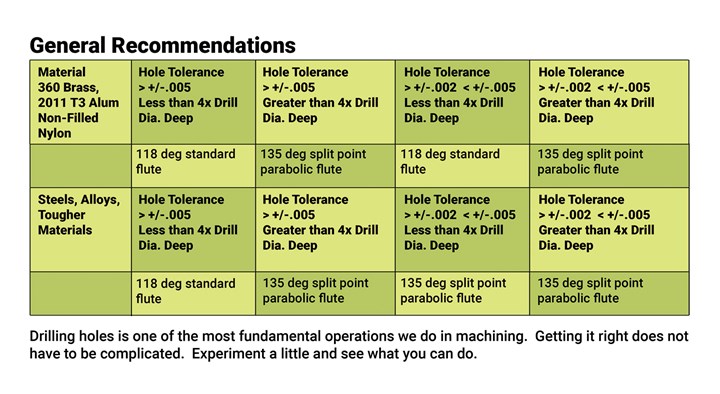

It is not recommended to try to achieve tolerances less than ±0.002 without reaming or boring. Here are some recommendations for twist drills for different materials often machined in our shops. In the light metals and those having high thermal expansion, it is recommended to use standard drills because holes cut tight. See chart below.

About the Author

David Wynn

David Wynn, MBA, is the PMPA Technical Services Manager with over 20 years of experience in the areas of manufacturing, quality, ownership, IT and economics. Email: dwynn@pmpa.org — Website: pmpa.org.

RELATED CONTENT

-

Rapid Methods for Determining the Weight of a Steel Bar (Imperial Units)

Counting bars in a bundle and multiplying by weight per bar allows a quick “reality check” on whether or not the tag weight is correct, or how much weight is left in the rack.

-

Steel Defects Slivers on Rolled Steel Products

Steel defects slivers are, by their very nature, “injurious defects,” and as such rejectable.

-

How Do We Fix American Manufacturing?

In America, many have lost sight of the fact that the object of the act of manufacturing is not merely the generation of maximum profit, but instead the creation of value.